How to Improve Doctor-Patient Communication

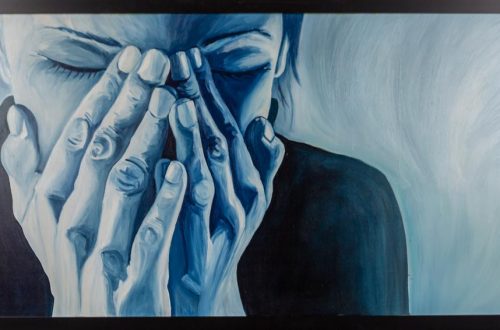

Dit artikel verscheen in The Wallstreet Journal op 12 april jl. Het belang van Luisteren in de gezondheidszorg wordt hier zeer goed uitgelegd. Ondanks alle technische mogelijkheden die er zijn en er nog aankomen, blijft het vooral belangrijk om mensen in de ogen te kijken en echt naar ze te luisteren. Artsen, verpleegkundigen, management, studenten geneeskunde, patiënten…we zouden met elkaar kunnen onderzoeken hoe we ons gezondheidszorgsysteem zo kunnen inrichten dat alles wat we doen start met het echt luisteren naar de mens die voor ons zit. Hierdoor krijgen we een beter beeld van de patient en zijn directe omgeving. Vanuit empathisch luisteren kan er echte samenwerking tot stand komen waarbij ieder een eigen goede bijdrage kan leveren aan kwalitatief betere zorg….#patientalspartner

With the advent of digital record keeping, I worry that we are losing the ability to look our patients in the eyes, listen intently to their fears and concerns and provide the support and caring that is so necessary for a relationship that promotes healing. I have always thought that the conversations with patients have the potential to be therapeutic or harmful. We can promote the kind of communication that enables patients to be better able to make difficult choices, to be more confident in pursuing the strategies they choose and to be more likely to achieve the results that they desire. And we need to avoid the kind of communication that alienates patients from the health-care system, inhibits them from honestly disclosing how they feel and what they need, interferes with their ability to make the choices that best fit them and reduces the likelihood that they will get the outcomes they desire.

And the loss of respect for the power of connecting with patients is not the fault of doctors, but seems to be a byproduct of the medical environment that we have created and the behaviors that we reward. Doctors lose also when relationships are a casualty of the production mentality that focuses intently on relative value unit, the currency of medical output, rather than the results achieved with patients—including the nature of the relationships.

Doctors, medical schools, hospitals, health-care systems need to find ways to foster an environment where everything we do starts with looking in our patients’ eyes and really knowing them.

The single biggest thing is to have empathy and to actively listen and communicate.

Doctors are not taught the importance of this skill very well in school. More recently, the reimbursement pressures and frequency of patients per hour are creating new “justifications” for some doctors to not connect with their patients at a deeper level. Brochures and iPads help with communications—but empathy makes the decisive difference.

The goal of good communication should be getting the best outcomes for patients. Seen in that light, the key for doctors improving their communication with patients is the quality of their communication with fellow clinicians.

That’s because good medicine is a team sport. Even the best surgeon can watch her patient die of an infection, accident or error because communication broke down among the team of professionals. Sorry to say, these deadly mistakes are commonplace and often the rule rather than the exception in many hospitals. An estimated one in four patients admitted to a hospital in America will suffer some form of unintended harm, and more than 500 people die from hospital mishaps every day. Moreover, an estimated 80% of serious medical errors involve miscommunication between caregivers when patients are transferred or handed off. Good team communication is life or death for patients.

Unfortunately, though health care is changing rapidly, traditional medical education focuses on teaching physicians to function solo, learning the details of diagnosing and intervening, but not so much the complexities of engaging disparate groups of clinicians, including nonphysicians, in common cause. The good news is we see new models of medical education involving practical experience for students working with a variety of disciplines alongside their patients, focusing on the art and science of good teamwork—but it’s all very new, and much more is needed.

While medicine is coming to realize the importance of physicians functioning as quarterbacks rather than as lone rangers, patients often expect Dr. Lone Ranger, and doctors hate to disappoint them or diminish their own reputation with their patients.

Patients have this expectation about doctors because they watch TV. In a given year, millions more people watch programs about hospitals than enter an actual hospital. With all due respect to my fellow commentator from “House,” hospital dramas reinforce public expectations of the doctor-hero, who needs little or nothing from his colleagues. Dr. House makes a brilliant diagnosis, then single-handedly intervenes to save the patient, often shooing away bureaucrats and the rare nurses haplessly getting in his way. According to a disturbing book analyzing media images of nurses, the character Dr. House sometimes even viciously disparages the few nurse characters that appeared in the drama.

In fact, in real life no patient should feel safe in a hospital where nurses are disparaged, because this is dangerous behavior on many levels. You wouldn’t know it from watching TV, but most of the care delivered at hospitals comes from nurses. When nurses are disrespected, the work they do is overlooked and not well supported—meaning 24-hour-a-day patient care is not a priority in the hospital. A terrific story in this month’s AARP magazine highlights how central nurses are in the safest hospitals. A physician who cannot communicate productively with a nurse—or puts them down the way fictional Dr. House does—cannot communicate effectively with patients, and in doing so, puts patients’ lives at risk.

Doctors need to listen more and talk less. When meeting with patients, doctors shouldn’t interrupt or dominate the conversation. Instead, doctors should ask open-ended questions to encourage each patient to describe his or her feelings and concerns about their illness. When doctors take the time to listen, the treatment decisions and care plans that they develop will better reflect their patients’ wishes; in turn, those plans are more likely to be followed by patients.

Toward the end of a visit, it’s important for doctors to carefully listen for any patient questions or concerns and to check for any misunderstandings or confusion. Studies show that up to 80% of the medical information patients receive is forgotten immediately and nearly half of the information retained is incorrect. To ensure each patient understands and remembers important information about their treatment, their doctor can ask him or her to describe the plan in their own words, a strategy known as the teach-back method.

Doctor-patient communication has changed in many ways since I graduated medical school more than 30 years ago. The recent introduction of electronic health records in the office, for example, requires many doctors to spend much of a patient exam looking at a computer screen instead of the patient in order to record information. This kind of distraction means it is more important than ever to listen carefully for what ails the patient. We have a tendency for a “quick fix,” which often means ordering a test or writing a prescription. Yet I fear, as in Adelaide’s Lament, the medicine never gets anywhere near where the trouble is. We need to be sure we are treating the symptom or problem that brought the patient in; for a cardiologist, as an example, the issue may not be the patient’s palpitations (or skipped beats), but the patient’s fear that these irregularities are a harbinger of a heart attack. So instead of prescribing a medicine to try to reduce the irregularities (which is not likely to be successful anyway), I may take the time to explain the electrical phenomenon of palpitations, and why it is nothing to worry about for most people.

In all of medicine, this is the simplest question to answer, but has the hardest solution to implement.

To get the biggest improvement in physician-patient communication, physicians need do only one thing: slow down.

In the U.S., the median duration of visits to office-based physicians is less than 15 minutes. That’s not very long to do all the black-and-white things that need doing. So it’s unsurprising that communication—being the pre-eminent shades-of-gray activity—is reduced to bare minimums.

Electronic health records have compounded this problem because they, too, demand communication time from the physician. And being legal documents, their need trumps the patient’s need. The next generation of EHRs will continue to have clunky interfaces and will therefore continue to steal time from the patient. Hopefully, the generation after that will actually improve the physician’s efficiency, and repay time previously stolen from patients.

Even after that happy day, however, time considerations will still dominate physician-patient communication. With the sole exception of military aviation, where flight surgeons integrate themselves into the flying activities of their patients and thereby enjoy unconstrained interaction, there will never be enough time.

Realistically, the best thing physicians can do to improve communication is put themselves into the heads of their patients. Done right, this results in using language that matches the faculties of the patient, minimizing distractions and interruptions, and anticipating questions.

One of my clinical heroes, Dr. Philip Tumulty of Johns Hopkins, wrote: “A pair of kidneys will never come to the physician for diagnosis and treatment. They will be contained within an anxious, fearful, wondering person, asking puzzled questions about an obscure future, weighed down by the responsibilities of a loved family, and with a job to be held, and with bills to be paid.”

Listening…(count to 10)…and listening some more. As harried clinicians, we have a lifetime of learning in our heads that we immediately try to use to diagnose and treat before we run from one visit or operation to another. This pressure will only get worse as the shortage of physicians grows. Perhaps the best thing we can do as doctors is to spread the listening, caring and health care to other members of the health-care team. For example, sometimes it’s better to have a pharmacist help a patient learn how to properly take their medications. Family counseling may be better handled by a social worker or clinical psychologist. A surgeon might need a physician assistant to check a patient after an operation while she is in the operating room. We physicians will have to let go of some activities that others might be just as good at (or better) to focus on those patients that need us the most.

I remember my initial surprise when taking my father to meet with a renowned oncologist to find that the first hour was spent with a PA. But she had, and used, the time to listen and understand my dad’s needs. The doctor came in for exactly the right parts of his care and the nurses who infused his chemotherapy were a lifeline. While my father eventually lost his life to that aggressive cancer, his care was better thanks to the nurses, PAs and hospice counselors who listened alongside and in collaboration with his physician.

Today, medical schools and teaching hospitals are working with schools of nursing and pharmacy to educate and train health professionals in interprofessional teams. This team approach will reshape medical practice in the future and help all caregivers do a better job of listening to patients.

Today, patients need “active” communications when it comes to the care they receive. This includes the opportunity for them to be heard, and education about their condition presented to them more clearly. Considering the expanding role of nurses and other clinicians in care delivery, active communication needs to occur throughout the entire care delivery team.

This type of approach supports shared decision making between care teams AND patients and their caregivers, and it’s already shown to improve outcomes.

Today, care teams are focusing on engaging patients and families in their care. They’re clearly explaining next steps of care, and ensuring opportunities for questions to be asked and concerns voiced. They’re also incorporating “teach back” strategies that ask patients and their caregivers to demonstrate that they understand post-discharge instructions by explaining them in their own words.

And they’re providing concise information on how to manage medications, explaining their purpose, how and when to properly take them, and possible side effects.

In all, this active communication approach has helped to cut readmissions among 448 hospitals by 8.4% in just nine months, reducing costs by $870 million.

Because every patient is different, doctors and nurses need to stress active communication to ensure they are understood. Making care decisions as partners can go a long way toward improving outcomes.

When doctors communicate with patients, there’s a series of unspoken choices they make—what to say and what not to say, who to include in important discussions, what counsel to provide, and what kind of follow-up care is needed. Many of these communication decisions may be influenced by assumptions and stereotypes about who a patient is, what “their story” is, and what their goals are. If the assumptions are wrong, it can limit a patient’s choices and compromise a patient’s health.

At EngenderHealth, we train doctors and other health-care professionals in more than 20 countries around the world, so they are able to provide women with high-quality care. Our success as a leading global women’s health organization is, in part, because the health-care professionals we train know that their interaction is more than just a moment in time: It’s about establishing a connection, ensuring that a patient understands all of her options, responding to what a patient wants and helping her achieve the outcomes she desires.

The fundamental prerequisite for good doctor-patient communication is time. If we doctors don’t take the time, patients will be dissatisfied.

According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, the typical adult primary-care visit is about 20 minutes. Let’s not kid ourselves: That’s not going to get a lot longer.

But we can have some influence on what happens during that time. In the past, clinic visits were largely devoted to the patients—addressing their symptoms, their problems and their concerns.

Increasingly, however, we have an agenda—things doctors are supposed to do to patients in order to demonstrate “high quality” care. Things like encouraging vaccination, further lowering blood pressure, ordering additional tests, adding new medications, initiating referrals, persuading patients to be screened (like mammograms) or discussing its pros and cons (like PSA). The list can get quite lengthy.

The physician and patient agendas compete for time. The longer our agenda gets, the less time patients have to raise issues that matter to them.

I’m not saying we should scrap all performance measures, rather that we should recognize that they come at a cost. Physicians are increasingly distracted by being compelled to meet the needs of the system—rather than the needs of the patient.

Thus I’d argue that the single most important thing doctors could do to improve communication is to help the system prioritize—and minimize—this competing agenda.

Not all performance measure are equally important. It’s a lot more important to find and treat the few people with really high blood pressure than it is try to get everyone to an “ideal” blood pressure (which has the unfortunate side-effect of leading some patients to fall). Some are just stupid. Given its mixture of benefits and harms, can anyone explain to me why persuading all women to undergo screening mammography has become one of the most prominent measures of how good our health care system is? Screening is a personal choice, not a quality metric.

Right-sizing the physician agenda may be the most important thing we can do to have our patients be heard.

Some doctors need to work on their interpersonal styles, which can be off-putting and unwelcoming. The patient-doctor relationship is very uneven, with the physician in a powerful position and the patient’s needing help but being worried about any visit. From the beginning of an office visit, every step has the effect of making the patient feel at the mercy of staff members. In practices without electronic medical records, the patient checks in, is asked for insurance coverage and then handed a clipboard with forms to fill out, often the same ones for every visit even when there are no changes, yet the patient can’t refuse to complete them. Then there is the wait in the waiting room, sometimes long, then the wait in the examining room. Requirements may be communicated to the patient in an indifferent or even mildly cool manner. At that point, a patient may be seen and asked questions by an assistant, who is likely to be friendlier but also may be a different one at every visit. The assistant asks questions and gathers information that will all be repeated with the doctor. The physician is always in a rush and may even try not to show that impatience and desire to move on quickly, although the eyes give that impatience away.

This is not just a problem in physician visits. How a patient feels and is often treated may be as bad or worse in hospitals, where the stakes are also typically higher. The importance of showing empathy with the patient was captured very well by Alan Siegel and Irene Etzkorn in the March 30, 2013, article in The Wall Street Journal. They reported on what a premier institution like the Cleveland Clinic has done to make visits much more comfortable and “patient centered.” Along with working on a warmer, more connected interpersonal style, doctors should be more focused on the provision of information about the condition(s) and what patients might do to make it better along with the doctor-prescribed drugs or treatment. Both of those opportunities, according to research, would lead to: physicians’ learning more about patients’ problems, more accurate diagnosis, more effective treatment and better “self management.” Doctors feel that they are already overworked and pressed for time, so correcting these problems, they believe, would only exacerbate their pressures and burdens, but, done well, such changes should also reduce patient dissatisfaction and treatment failures.

With the decline in the number of primary-care physicians, relative to our growing and aging population, even the best doctors will be under more time and financial pressures. With the right training and more extensive use of care teams (not to repeat questions or care but to substitute professionals with clear protocols and arrangements), doctors can focus more on those complex questions for which their training is most suited. They will be happier, more empathetic and patients will benefit.

If you want doctors to improve communication skills with patients, then pay them for their time to do it. Doctors are very good at figuring out what the system rewards. The system financially rewards “doing things”… i.e. prescribing and procedures. So, not surprisingly, that’s what doctors do well.

Now, if the system were changed so that doctors were paid for the time it takes to talk and communicate with patients, then doctors would do that well.

Change reimbursement and change behavior.

I’m going to default to the practical advice posted at railroad crossings: Stop, Look and Listen. Stop facing the computer. Look at your patients while you talk to them. Listen for more time than you talk. Body language can say more than words, but you’ll miss it if you aren’t looking, and your patients can’t ask questions if you don’t give them space. How does your patient’s expression change when she describes her headaches? Does he avoid your eyes when he says he’s monitoring his diabetes? It sounds so obvious—ask anyone who’s tried to ferret out the whole truth from their teenager over a cellphone call or text message and you’ll hear the same. Still, as electronic medical records have moved from rare to obligatory, more of the physician-patient conversation is happening with some portion of the doctor’s attention on the screen. It’s understandable, too. Physicians today are pressured to see more patients in shorter visits even as disease management becomes more complex and documentation standards become more rigorous.

This push for higher efficiency is driven by a backlog of waiting patients (the Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a 45,000 shortfall of primary-care physicians by 2020) as much as economics. Some billing codes even account for extra time spent in face-to-face conversation. Unfortunately, the realistic limits of time and stress mean a lot of that face-to-face time is actually spent face-to-back. But a patient who leaves with unanswered questions or uncertain instructions will more likely end up returning to the office or being admitted to the hospital, so those extra face-to-face minutes might be the ultimate health-care bargain.

One of the most effective things doctors could do to improve patient-provider communication is to listen. Studies show that physicians have a tendency to interrupt patients before they’ve had a chance to tell physicians what’s on their minds. For example, work by Beckman and Frankel found that patients were interrupted an average of 18 seconds into their opening statements and allowed to complete their initial thoughts in less than 25% of office visits. A more recent study found that physicians interrupted patients after only 23 seconds.

As a physician who practiced primary care for 35 years, I well understand the tyranny of the clock. The need to move patients through on a 15-minute schedule forces even the best-intentioned clinicians to push patients to “get to the point” as fast as possible. But the result is neither a satisfied patient nor a satisfied clinician.

Better listening has the potential to improve patient satisfaction, increase adherence to prescribed treatments, and reduce the risk of medical malpractice claims. Utilizing electronic communication is one strategy for allowing patients more time to “be heard.” While a recent Commonwealth Fund survey found that only 21% of adults with Internet access could communicate with their doctors by email, reports suggest that those who can generally find it extremely beneficial. Perhaps it is the continued advance of information technology that will allow us to practice one of our most valuable skills as doctors: Listening to others.

When doctors meet patients, there is a tendency to “get down to business” and solve the medical issue at hand. This transactional approach frequently leaves the patient unsatisfied and with the sense that they were not heard.

Doctors can improve their communication by seeking to understand the perspective of the patient. Attentive listening or the careful study of facial expression and body language can go a long way, but this critical duty can be simplified by always asking patients three simple questions (I.C.E.):

Understanding the patient’s response to I.C.E. creates attunement, not agreement (e.g., a doctor need not—and generally should not—fulfill a patient’s expectation for an antibiotic for their sore throat). It signals “I hear you, I understand you, and I respect what you are saying.” Every illness—even the common cold—has a biological and psychological dimension. When the doctor understands what the patient believes, fears and wants, they can both “get down to business”—the business of healing the body and the mind.

The most important thing doctors can do to improve their communication is to know their audience—what patients and families are dealing with and need beyond tests, medicines and procedures.

The days of Marcus Welby, the genteel 1970s TV doctor who played a chief care coordinator, are over. Doctors no longer informally discuss their patients at the doctor’s hospital lounge or formally assure that information critical to their patient’s care gets to the right place at the right time for the right action. No one is. The patient and family are left holding the bag.

The shocking truth is that once we whisk patients out of our hospitals and offices, they are “home alone.” A recent study of more than 1,600 by AARP revealed the shocking news. Family caregivers are giving shots, caring for wounds and delivering complex care with virtually no training—actions that would make a medical student or nursing student tremble with fear. Doctors think when they order home health-care services that a nurse will magically appear at the patient’s door when they get home. This doesn’t happen and families are on their own most of the time. Most have to train themselves, are fearful of hurting loved ones, and are often blamed when a patient is readmitted to hospital.

America’s greatest CFOs are not financial leaders, they are the Chief Family Officers, who are typically women, who get the prescriptions filled, play the frightening role of a caregiver with no training, and shuffle their family members between rushed caregivers who are often more concerned with throughput than outcome. They find themselves the courier of medical records and responsible for handoffs. Their needs are so acute that we developed the CareMoms program to teach families through our CareUniversity. Families are ready to step up and learn content. They would have loved to have a Marcus Welby, however, they are living “home alone.” The best physician communicators will deliver what this audience needs.

Encourage patients to ask questions. Although medical schools are training doctors to listen and be more empathetic, the environment and power balance remains much like it was decades ago. Doctors’ offices can still intimidate and inhibit patients from asking pertinent questions. This is particularly true when socioeconomic disparities are wide between the doctor and patient. But the effects are so pervasive that even other doctors sometimes cannot find the courage to question their personal doctor! Clearly a confident doctor helps foster a therapeutic alliance and alleviates decision anxiety, but an intimidating doctor may cause the patient to clam up. When patients remain silent it is impossible to know what’s on their mind. Patient insights are critical for accurate diagnosis and compliance.

I discussed this issue with a good friend, Professor Dan Ariely, a leading behavioral economist. We agreed that medicine should seek solutions from experts outside the medical field to optimize the entire communication environment (not just communication skills). There was one quick solution that we both felt would work well—doctors should make it a requirement that each patient must ask at least three questions before the visit is over. This will ensure that patients don’t stay silent, help the doctor know how well the patient has understood the issues, and make it easier for the patient to ask additional follow-up questions. AHRQ’s “Questions are the Answer” website has tools to allow consumers to generate a list of personalized questions.

Voltaire famously noted many centuries ago that one should judge a person by the questions they ask, not by the answers they give. As we approach the era of personalized medicine, we need to teach our patients to ask the right questions.

Every pediatrician I know has a corkboard in his or her office festooned with drawings from patients. The pictures are generally charming, poignant and funny.

A few years back, a pediatrician received such a drawing from his 7-year-old patient. It was charming and poignant, all right, but it was decidedly not funny. The picture was later published in an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In it, the 7-year-old girl is shown sitting on the doctor’s examination table. In one corner of the room is the patient’s mom, holding her baby sister; next to them her older sister looks on. The doctor is on the other side of the room, hard at work.

The problem is that the doctor’s back is to the patient. He is looking at his computer screen.

We simply must computerize American medicine. Health care is the most information-intensive of industries, and yet—until recently—most information was recorded on paper in often-indecipherable handwriting. This meant it could not move from office to hospital, or from hospital to nursing home. Nor could it be made available to the ER across town to help manage the patient with a stroke or after an automobile accident. Paper-based records also rendered the process of gathering information to measure the quality of care, or improve it, a laborious and error-prone business. And the kind of decision-support that we’re used to in the rest of our lives—alerts to remind us to buy an anniversary present or catch a flight—were unavailable to clinicians. These alerts have the potential to prevent doctors from prescribing medications to which patients are allergic or to prompt them to order the most effective treatments for sepsis or heart attack.

While I’m tempted to say that the most important thing we could to do to improve communication is remove the computers, that’s not right. We need them. But, as physician and author Abraham Verghese has written, in today’s medicine, “The patient is still at the center, but more as an icon for another entity clothed in binary garments: the ‘iPatient.’ ” Sad, but too often true.

The most important thing we can do is to remind our clinicians—and teach our students—that the real patient is more important than the iPatient, that the human connection is essential to the art of healing and that that 7-year-old girl, and every patient we see, is observing our every move for signals that we actually care about what happens to them.

The one that makes a huge difference in my ability to better understand and address my patients’ needs is for me to ask each patient, “How can I be of greatest help to you today?” at the beginning of each visit. Then I stop and listen to their answer. This allows me to immediately focus on what matters most to them, and they feel listened to, understood and respected.