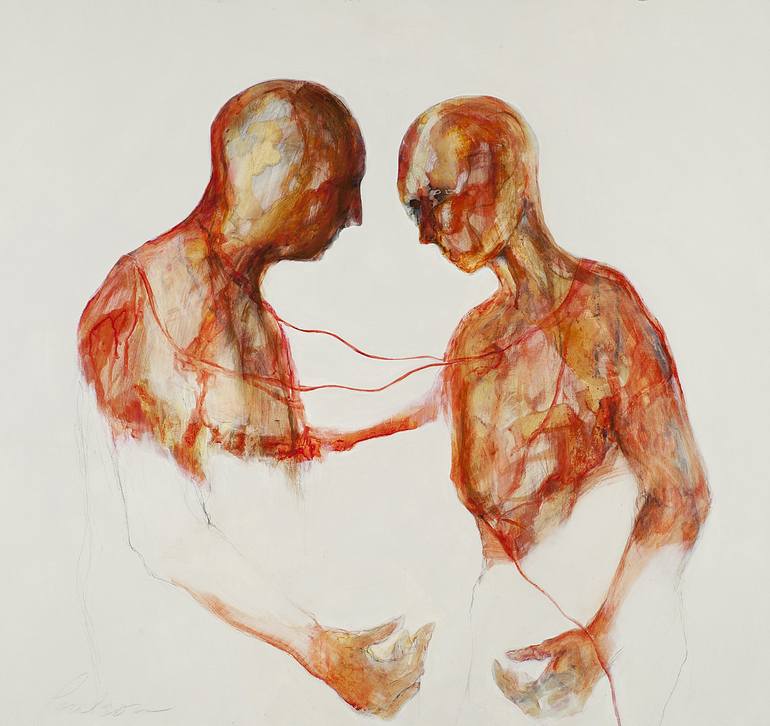

What is connection?

Connection is a word that is often used, but what does it actually mean? Philosophers, thinkers, and writers have tried to unravel this concept throughout the ages. Connection is more than a conversation or a shared moment; it is a fundamental human desire to be seen, heard, and understood. But how is it that one person feels a connection in a space, while another feels disconnected or uncomfortable?

Philosophical reflections on connection

Philosophers have long pondered what it means to connect. Emmanuel Levinas, a philosopher focused on ethics and relationships, holds a special place in this discussion. Levinas teaches us that true connection arises in the encounter with the Other. For him, listening is not merely hearing words; it is an ethical act, an opening of oneself to the presence and needs of the Other. The essence of connection lies in seeing the other as unique and irreducible – someone who cannot be simplified into a role, function, or stereotype. In the face of the Other, Levinas invites us to take responsibility, to truly listen, and to be present without imposing our own narratives.

To listen, in the Levinasian sense, is to enter a space of profound humility. It is to make room for the Other’s voice. This kind of listening creates the possibility for deep connection because it acknowledges the infinite depth of the Other’s humanity. Levinas’s philosophy reminds us that listening is not passive; it is an active engagement with the Other that demands attention, care, and responsibility.

Martin Buber, another significant thinker, describes connection in terms of “I and Thou.” He distinguishes between the “I-Thou” relationship, in which we see another as a living being we deeply encounter, and the “I-It” relationship, in which we view the other as an object. According to Buber, connection only emerges when we have the courage to regard the other as truly real – with all their complexity, vulnerability, and strength.

Why does one feel connection and another does not?

Interestingly, connection in the same space can be felt by one person while another experiences that space as empty or uncomfortable. This difference can be explained by both internal and external factors. Maurice Merleau-Ponty highlights the role of physicality: how we physically relate to others, how we breathe, our posture, even subtle touches or glances, all contribute to the degree to which connection is felt. When our senses are attuned to the other, connection can feel almost organic.

At the same time, Ludwig Wittgenstein emphasizes that language can be both a bridge and a barrier in connection. When our words fail to resonate with one another or when misunderstandings arise, our sense of connection can be disrupted. In such situations, silence can be healing, as it creates space for mutual attunement without words getting in the way.

The context of the space also plays a significant role. Hannah Arendt suggests that we can only truly experience connection if we are willing to open ourselves to the dynamics of the space. The history of a place, the energy present, and our own state of mind all influence the extent to which we feel connected. If we close ourselves off, for example, through distrust or fear, even the most crowded space can feel empty.

Connection as a mirror

Connection also demands something of ourselves. Jean-Paul Sartre argues that the gaze of the other confronts us with who we are. This can be uncomfortable because it makes us aware of our own vulnerability. But within that vulnerability lies the potential for genuine closeness. It takes courage to show yourself, to not turn away from the intimacy of an encounter.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty adds a bodily dimension to this. He describes connection as something also experienced through our bodies, in the way we relate physically to the other. Our posture, our touch, even the way we breathe in the same space, all contribute to creating connection.

Connection and language

Ludwig Wittgenstein points out that language can be both a bridge and a boundary in connection. Words give us the ability to share, but they can never fully capture what we feel or mean. The true power of connection, according to him, lies in the nuances of what is unsaid, in the silences between words.

A quit ending

We cannot grasp or control connection; it happens in moments of openness and mutual presence. Perhaps it is enough to notice these moments when they arise, to cherish them without needing to define or capture them. In the end, the connection might just be the quiet act of being present – for the Other, and for ourselves.

Art: Karen Poulson